A VISION FOR PAN

KEY NOTE & HARMONIZATION

What is our vision for the steelpan? It has come a long way but where will it be heading in ten years? How can we use it to help our youth and society? Does it have a capacity to heal? Those international friends with whom we have shared it seem to appreciate it much more than us. How can we deepen our appreciation of this instrument, the history of the movement and the quality of music produced? How are we teaching it? Are traditional Western research systems appropriate for studying this instrument? How do pan men and women today feel about its future? Perhaps all these questions can be answered by means of a fresh vision.

My personal reflection on this quest for a long-term vision for pan is geared specifically to Trinidad and Tobago thinkers in search of a new ethos for cultural flourishing.

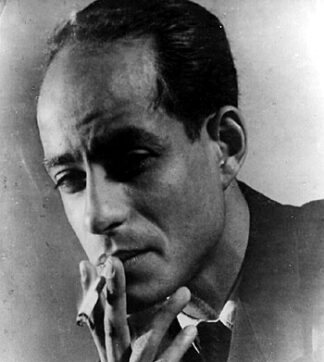

The late Aimé Césaire, renowned marxist Martinican poet, playwright and politician commenting on the historical class struggles of Caribbean people, wrote in Présence Africaine: “In the circumstances through which we are passing, our art must become a sacred art.” Césaire who died in 2008 was also one of the founders of the negritude movement. But why as early as the fifties and sixties would a presumed atheistic communist have pointed us in the direction of the sacred? At most, there seems to be a contradiction in terms here, or at least a paradox. In Africa, the drum is considered sacred and connected to tribal religion.

Although a far twist of fortune from colonial and cultural biases against pan, pan music today is played in churches. While it can be classed as a melodic evolution of the drum, does this development suggest that pan has reached the level of sacred art?

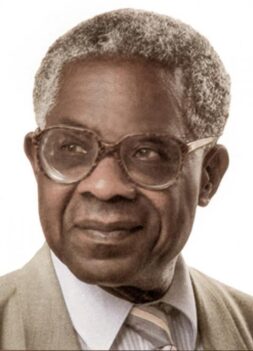

Beyond Césaire’s commitment to issues of race, there came a different perspective from another intellectual elder, Wilson Harris, who took a higher road, so relevant to our quest for a wider vista. As this late Guyanese writer and critic had put it, if we can accept that the West Indian is a cognitive minority in the world and not a racial one according to the canons of predominant scholarship, then we understand that the main choice for Caribbean peoples and mankind as a whole in the face of rising global temperatures and conflict, continues to be between mortal and immortal values.

Immortal values point us back again to the realm of the sacred; we have come full circle. Both intellectual luminaries Césaire and Harris have set up, in my view, important signposts for a possible vision for pan. If we accept Césaire’s appeal to the direction of the sacred, it does come with a built-in cautionary note, for it suggests that without a sense of the sacred there is a strong possibility our artists could be wasting away their contemplative faculties, tumbling into a meaningless, materialistic and chaotic world of forms. If we accept Harris’ higher road, avoiding the colonial trap of ‘divide and rule by race’, we might be morally and significantly freer to fashion our destiny by means of this instrument. In fact, we could say that certain associations with the notion of race fail to capture the esoteric dimension peculiar to the unique genius of Antillean man, a distinctive phenotype.

In the fifties and sixties, there was much political talk about the integration of the West Indies: leaders discussed the possibility of the West Indian Federation both before and after the independence of Jamaica, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados and other islands. While at the political level this unity failed, it came to be achieved during the seventies at the level of sport, in cricket. Culturally however, it was the steelband, a new sound from a particular rhythm of life in Trinidad that facilitated this unity at the level of being. Many English-speaking islands would absorb it into their carnivals.

More to it, Trinbagonians in their cultural affairs have traditionally resisted viewing themselves from outside for validation, from, let’s say, the tourists’ eyes. It would perhaps be more appropriate for us to look within, that is, from a perspective directly consistent with our gifts and native traditions – a vantage point from which pan men and women have always looked out onto the world.

I have chosen a category of being where the most valued experience occurs inside the experiment and not outside of it; one in which music - the steelpan - is resoundingly integral to an understanding of ourselves as immortal spirits in harmony with nature and the Author of nature.

This re-connection is our new key note, if you will, a pitch in the rhythm of life rightly ordered, of national identity, community and international sharing, centred on the first principle - dispositions which were strikingly evident in the forties among the pioneering inventors of pan who were keenly aware that history was being created in their midst with the forging of what would become our national instrument. In an interview with Leslie Slater, the late Ralph MacDonald ruminated:

"Promoting the sound of the pan music as something vibrant, something new, something different was definitely what I had in mind,” he says. Then out pours the essence, the very core of his conviction about the steelpan’s true place in the cosmos. “I’ve been fortunate in my life. I’ve been around the world, seen many different things, really nice things. And to me that pan…that pan is a wonder of this world." (“The Pan Sound’s Big League Booster”, Pan, 1985)

For MacDonald, pan has a cosmic dimension; it symbolizes a central principle penetrating and connecting all of life: here we approach the sacredness of our art. This lofty ideal, certainly not a naïve one, is truly lived out and reflected in collective work without pay to build homes or farms, or in the financial cooperative called sou-sou in Trinidad. Its social features also appear in Marie Galante as comoi, in the Dominican Republic as convite, combite or corvée in Haiti and again in Trinidad as gayap. In both Venezuela and Trinidad, gayapa is a root word for this sacred science in which so much community sharing is bound up.

In our regional context therefore, it would be out-of-step to assume a self-defeating taboo against spirituality, so tempting today in academic circles. University students the world over should be inoculated against this anti-spiritual bias, where left-leaning ideologies would no longer be harbingers for the loss of faith. “Ah sen meh chile to university and now he doh believe in Gord anymore. Look at my cross, nah!” Be it in Timbuktu or Italy, to lose sight of the fact that religions first established universities, is already to view the world through a topsy-turvy lens. In our Caribbean context therefore, to lose our sense of the sacred would also be to lose the very essence of our creativity.

This shift in our perception calls for some examination and critique of our assumptions in traditional methods of study. When an atheistic anthropologist, for example, studies a people, does he assume that his subjects are devoid of any higher thought, natural philosophy or contemplative awe? With what personal instrument would he participate, examine, assess or catalogue their abstract experiences? Is anthropos, the study of the human (or Son of Man in the original Greek), without spirit, or is this yet another contradiction? This reclaimed inclusion of the transcendent in a fresh outlook ought really to be useful to anthropologists and ethnologists to demonstrate and document, if used properly as an instrument of observation and participation, the mystery, wonder, awe and joy arising from art, music, work and communal life in Trinidad and Tobago. This advantageous point of view, of the experience being inside the experiment, is quite obvious to foreign pannists who, at the behest and consent of bandleaders, immerse themselves in local steelbands for Panorama competitions every Carnival. They discover that ‘she who tastes, really knows.’ Therefore, scholars should do the same.

The Caribbean community possesses a unique worldview. Jean Baptiste Roumain, Haitian author, poet, novelist, essayist, political activist and diplomat, defined his sociological boundaries early in the game when confronted with this way of seeing:

“Cultural values will be considered as they are reflected in three spheres: intellectual life, art and religion. This division, I may say, is often artificial in Caribbean countries where phenomenon are closely interwoven and tend to be complementary.” (Caribbean Cultures, UNESCO, 1982)

It is crucial to reintroduce this interwoven and complementary approach to the study of pan to provide up-and-coming musicians the option to produce centering works of lasting indigenous archival value. It is no secret that they have already been doing so amidst a lot of dissipation and depravity disguised as culture. Maybe the time will come, is probably already here, when we may need a radical shift in how we impart immortal values through our compositions.

From programme initiatives launched in recent times, it is clear that highly therapeutic effects are derived from the panyard as a base for community bonding, music education and literacy, a harmonization with wind, brass and string instruments as well as the inculcation of discipline that stems the tide of criminal behaviour among young males in particular. Senior Counsel Martin Daly has been promoting this use of panyards for male mentoring for some time now, while former Director in the Culture Division Ingrid Ryan-Ruben in the then Ministry of the Arts and Multiculturalism had the foresight, wisdom and experience to craft and deliver programmes such as Music Schools in the Community in panyards. The documented benefits to young persons learning to play an instrument in that programme include improved memory, academics and linguistic skills, not to mention the critical role of connecting families and creating bonds of friendship and solidarity. From the scientific research angle, there is the cognitive benefit of a marked increase in the corpus callosum, the bridge connecting the left and right hemispheres of the brain – yes parents, your children do get smarter when learning to play an instrument.

It is no accident that clashes and warfare between early steelbands of the late fifties - their first negative social stigma of violence, colonial snobbery and heavy-handed hounding by police - was transformed over time into the diamond of respectable performances on the stages of Carnegie Hall and esteemed festivals everywhere. If we are honest, we must admit to a lawless and inconsiderate streak in our nature, which was infecting unseen and of late has visibly grown to a murderous and cancerous degree, threatening our very present and future. Pan, at this juncture in history, unwittingly becomes a more urgent panacea for quelling crime in Trinidad and Tobago and the Caribbean. Surely, we treasure the living memories of our elders who know too well that pan pioneers were once severely tested and tempered in the crucible of suffering. Sterling Betancourt, pioneer, arranger and musician, remembers metaphorically:

"Severe abuse (with sticks, pieces of iron, or whatever) of these surrogate ‘instruments’ formed indentations on the surface, and, by chance, notes albeit with pitch as harsh as the social demands of the war on the poor. " (“Vignettes of History”, Pan, 1985)

It would be of inestimable value if we collectively acknowledge a divine hand in the evolution of pan and how even the interior character of its exponents came to be refined and uplifted in less than a century. What a paradox! One could say, both providentially and in hindsight, the pan movement has been tremendously blessed: “the lowly He hath exalted.”

We should laud and support progressive developments that herald a vista of cultural activity for artistic development, male and female excellence and ever-deepening national identity. This process is already underway. Milestones such as the evolution of the stunningly gifted National Steel Symphony Orchestra through its previous iterations; the well-appointed pan theatres replacing rustic pan yards; the establishment of trade associations; secondary school level education in pan construction; manufacturers such as Panland followed by Music Instruments of Trinidad and Tobago Company Ltd (MITTCO) hoping to become the Mecca of pan production; steelband music on the curriculum of North American, European and Japanese schools and universities as well as the creation and patenting of the Genesis pans - are luminous beacons of public and private sector investment in the instrument with its ever expanding appeal.

Pan is officially celebrated as the only musical invention of the twentieth century arising out of a New World experience not based on any previously established instrument. Historically, its scope and impact have been compared to that unique brand of Christianity that harmonized in ancient Ethiopia via Axumite and Greek Orthodox liturgical expressions. It is often compared to the emergence of New Orleans jazz as a harmonization among Creole, Afro- and later Euro-American peoples contributing to the creation of a space for mutual communication, experimentation, innovation and artistry. Here again Wilson Harris sees the West Indian artist and the steel pan as potent agents of change:

"When the toy-man, the exploited man, becomes aware of original rhythms within the apprehension of his world, contradictions are bared in a manner terrifying and yet containing the secret of change…. The Trinidad steelband has been deemed ‘not respectable’ … the structural potential and peril of the world is related intimately to the human being. That to my mind is the situation of the West Indian artist, the situation he has to express, the architectural problem that confronts him.

Who or what is the creator of man, the human being? Here is posed in a question the great insecurity about origins that troubles modern man. This question contains another question of ‘interior-cosmic and exterior-cosmic’. Man is frequently overwhelmed by the immense and alien power of the universe. But within that immense and alien power the frail heart-beat of man is the never-ending fact of creation. Man’s survival is a continual tension and release of energy that approaches self-destruction, but is aware of self-discovery." (Tradition, the Writer and Society)

Self-discovery is at the heart of this vision, which outgrows the destructive habits of violence and profanity, so easily recognizable as the products of impure and unschooled consciousness, to be gracefully discarded. It cures the soul-wound of racism, oppression and deep colonial hate. It outgrows even the misuse of religion for one’s own purposes: many in the cultural industries know what I mean, especially the temptation to hurt a perceived enemy spiritually, which is nothing more than rank evil.

Rather, we must focus on building a civilization of love: the artist must therefore be rightly disposed to do so, since he or she has an awesome social responsibility, is fully equipped with empathy, vision and ‘enemy love.’ Daily discourse on the streets of any major centre of cultural activity reveals that Trinbagonians also share a vision of ‘unity in diversity’ where their happy music is concerned, a vision embedded in pan as an instrument that transcends class, race or country of origin. Above all, we must plumb the depths of that endless well of creativity, long bestowed on this land, so as to forge a new heart, a new way of seeing. The only constant thing in life is change. Long live pan and let it foster harmony!

by

Mark Andre Augustus

Dedicated to my father Earl Augustus who encouraged me in

spiritual, intellectual, musical and artistic endeavours.

Also dedicated to the memory of Prof. Jay Ruby

who vehemently rejected this vision in my film proposal

for his Film and Anthropology course at Temple University in 1989.

Let all injury be forgiven. May he rest in eternal peace.

Special thanks to Teresa Dookharan for editorial assistance

© April 29, 2023

*